The thing about Filipino families is that togetherness is everything. No matter what is going on, togetherness is the priority. It’s what we strive for, look forward to, push everything else off the plate in the name of: togetherness.

When family members have passed, it’s togetherness that glues our sanity together. At weddings, the fun melts into some kind of semi-organized rage, minus the mosh pits. The explosive energy can be life-giving, life-saving even.

The two bookends of the past week, both calling for togetherness, couldn’t have been any more different in nature.

On my maternal side of the family, my only surviving grandparent, my Lola, underwent a partial mastectomy for cancer. She’d never met Isaiah and my memories of time spent with Lola were dated back to the 90s. After much discussion and re-organizing, I decided to take Isaiah on his first flight and meet more family.

My parents and sister traveled as well. My aunts, uncles, and cousins that lived there were happy for an unexpected reunion. And while the reason why we were there was sobering, the atmosphere couldn’t have been any more of the opposite.

I arrived in Atlanta Monday afternoon and eager to see Lola. I carefully stepped down the stairs with Isaiah and immediately saw my Tita from the Philippines. She swiftly embraced Isaiah and urged me to go greet Lola. I did. Her face looked more full of life than I had ever seen. Her eyes were bright, her cheeks rosy, her body looked strong. “Hi, Lola,” I breathed into her silver hair as we embraced. “Oh, hija, I miss you,” she replied in her thick accent. She chuckled and talked quietly in Tagalog when she saw Isaiah, her newest and youngest great grandchild. She bathed him in her affections.

Within ten minutes of my arrival, Lola, stubborn as a mule and spiritual as the Dalai Lama, wearing her tsinelas and apron, brought me a bowl of Tinola, homemade soup of vegetables, potatoes, and chicken. Lola, about to undergo surgery, insists on cooking for me, the new mother who is still nursing her baby. My father, mother, and Tita echo Lola’s intention: it’s the soup bones that help a new mother regain her strength. “That’s what my father cooked for my mother,” my father reminds me, “she gave birth eleven times and had this soup every time.” Even though I wasn’t really hungry, I ate. It felt wrong otherwise.

The table was slowly crowding itself. Plates of tinola, adobo, rice, pancit, and – out of nowhere – a plate of Mexican chicken appears. “Lisa, have you had this?” my Tita is about to give me a piece of chicken. I smile and decline. But not before my Tita slams a huge bowl in the middle of the table: FRENCH FRIES.

My Tito, who has the fastest stride in the south, quickly walks in the room and inspects the table, “Oh these are poisonous! They’ll kill you!” as he grabs a handful of french fries and shoves them in his mouth.

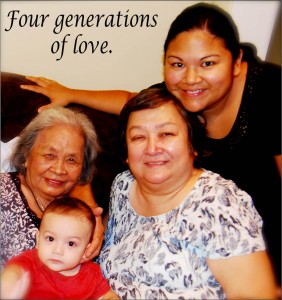

It was the first of many meals we shared together. Always talking, re-telling, remembering, laughing, and prompting someone else to share their thoughts. Uncharacteristically, I just sit back and observe. Smiling, taking in the craziness, loudness, and overlapping conversations that no one can understand. The mixing of English and Tagalog and a little bit of Spanish. Seeing Isaiah sandwiched between his Lola and greatgrand-Lola gives me a moment of grace that I can’t really explain. I just thank God.

I’ve heard that children of immigrants carry the traditions and history of their family with them, but oftentimes, much of it dies when they begin their own families in westernized cultures. Sadly and inevitably, that has begun in my life. For as much as I try to keep pieces of my culture alive, without an active support system that continues to remind and teach you of your background, those once vibrant pieces of culture become memories.

The glorious part of it, though, is when you are reunited as family. It’s like a shot of Filipino adrenaline to my blood.

The endlessness of cooking. The overabundance of everything -talking, drinking, laughter, eating – and sleeping until the cows come home. Story-telling. More laughter. Tanglish talk.

The next few days passed slowly. Everyone was busy with transporting and taking care of Lola while I was just trying to keep up with Isaiah in new surroundings. Isaiah, unfortunately, had some kind of allergic reaction to the dogs. It’s doubly unfortunate because he thinks dogs are his best friend. His smile lights up the room when he sees those four-legged furballs. Keeping him away from the canines was a sad job. It was like holding a treat a few feet out of his reach for four days.

My Lola is Illocano, from the Illocos Norte region in the Philippines and it’s customary that when a child enters your home in Illocos Norte, you give the child money so he or she will never experience poverty. Four days had passed and we were saying goodbye, both my Tito and Lolo stuffed envelopes of money and ran it over his silken, chubby limbs for blessings of abundance. Isaiah thought it was some game called SNATCH THE ENVELOPE AND EAT IT. I stood by and watched the tradition of my bloodline reach my offspring. And while I have no such traditions in my house, it reminded me again of why I was so proud of my heritage. The hospitality, the history, the love, the togetherness.

Family, the inescapable stress and medicine of our lives, gets us through the darkest hours of the unknown.

I flew home with Isaiah, a deep tiredness in my bones from holding him so much and silently pleading with him to behave on the plane. The heart of me connected to the heart of him. We came to an agreement: if the plane ride went well, I’d let him chew on his beloved breakfast spoon, uninterrupted, for however long he wanted. DEAL.

We came home long enough to get one night of rest before taking off to Columbus for Nick’s long awaited half marathon.

Nick, training for ten weeks, had arrived at his big day and my brother and his family, along with our sister, all traveled to Columbus to cheer Nick on. Also running were his sister, Kelly and brother Keith. It was a family affair.

In Columbus, I was too exhausted to do much of anything but observe the togetherness. The way the Borchers talk, laugh, discuss, and prompt each other to tell stories is completely different than how my family does, but the result is quite similar: laughter, bonding, sharing.

I thought of how lucky Isaiah was to be locked into so many webs of families, all different from one another and uniquely situated in geography, life experience, and culture. I thought about how blessed he was to have greatgrandparents, grandparents, and parents who would never let a raindrop hurt him. I thought about how my mother traveled across oceans, leaving her mother, so she could work for a better life and, years later, my Lola would come to this country as well. I thought about how there was nothing either my mother or Lola wouldn’t do for family.

And I watched Nick’s parents and Jay cheer Nick on, how they took turns holding Isaiah. I watched my siblings mingle with Nick’s siblings and how amazingly beautiful families can look like when they’re celebrating the achievement of someone they love.

Families come together in times of worry and sickness, praying that death is many years away. Families come together in times of livelihood and celebration, praying that wellness and health continue to carry us to more marathons and dominating physical challenges. The unity, at times, seems unbreakable. Almost divine.

Individuality is one of my signature characteristics, but as I age, I am coming into deep awareness of how limiting and isolating extreme individuality can be. It comes at a great price. While I have a deep, almost intrinsic need to sometimes be alone in my thoughts and away from the world, I am learning how much I need family. I may not know it. I may not request it. I may even push it away, but the need for togetherness pulses strong in my blood. Families are far from perfect, but, luckily, perfection is not a prerequisite for occasions of recovery, healing and joy.